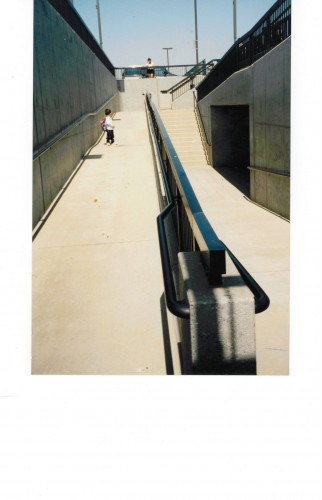

A little less than 20 years ago, some friends and I stood in front of the Fullerton City Council pleading with the Redevelopment Agency to build a pedestrian underpass at the train station instead of a steel bridge overpass. We had three reasons. The first was expense: an underpass was about half the cost of a bridge. Second was the matter of practicality and convenience: it is easier for a pedestrian to climb 24 steps versus 49; not to mention the cost of maintaining two elevators. Third, the bridge was going to tower over the Historic Santa Fe Depot – a real incongruous pairing and one in which the Depot suffered.

When the question was asked to the city staff during the public hearing about the possibilities of an underpass the Fullerton Redevelopment Manager Terry Galvin answered that an underpass would be too dangerous and could end up smelling like urine and besides, “nobody builds underpasses.” He even dug up an incident (and only one!) where somebody got stabbed – in Raton, New Mexico. Ooooooh, so scary! The fact of the matter is that an underpass would have been a mere 50 feet long – a little more than half the distance from home plate to first base!

The staff also dismissed Vince Buck’s brilliant idea of using the existing Harbor grade separation to get people from one side of the tracks to the other, a solution that would have been the most practical and cost efficient of all!

What has always bothered me about the city staff is that when they want something they will not give the city council all of the pertinant facts to make an intelligent decision; or they will deliberately inflate the project they want and diminish options they don’t want. And then the city council does not hold anyone on staff accountable for the messes they create. And that my Friends, is the history of Redevelopment in Fullerton.

A couple years later I was at the Oceanside train station and guess what?

Of course lots of local Metrolink/Amtrak stations now have underpasses including Orange, Tustin, Laguna Niguel and many others. Money was saved, citizens were spared visual monstrosities, and maintenance costs were minimized.

But in Fullerton we have Molly McClanahan (who voted for the bridge), and her immortal words: hindsight is 20/20.

Almost twenty years later and the City of Fullerton doesn’t even seem to bother with the graffiti etched into the elevator towers’ glass.

The word in academic circles is that the CSUF is busted. Or at least it doesn’t have the wherewithal to swing a deal under consideration to buy back property it once owned across Nutwood Avenue.

The site is the current home of Hope University and it contains some wonderful buildings designed and constructed as part of a modernist master plan. The rough idea was that the CSUF Auxiliary would acquire the property, and, after a lease-back period to Hope, would start knocking everything down – presumably to throw up more out-of-scale, hideous erections. We first wrote about it here. And our expert consultant defined the term “exaggerated modern” here.

So the recession may have a silver lining anyway – at least as far as historic preservation is concerned, but we shall see what the future brings.

In the meantime, just to the south, the giant hole in the cityscape left by the demolition of perfectly fine modern-style buildings to make way for the Jefferson Commons swindle are a silent yet eloquent testimonial to the lack of foresight exercised by our elected leaders.

Dear Friends, we have just received this poem from a life-long Fullerton resident who goes by the web-handle of “Bushido Poet.” Apparently BP is a ninth-level haiku master. So when he haikus, we listen:

Rain patters my roof

Cold winds rattle the window

A braying donkey

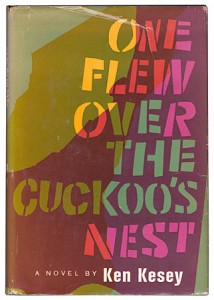

Last Saturday the hubby and I dropped in on the Maverick Theater to see their production of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” a theatrical adaptation of Ken Kesey’s novel.

Now I’m not much of a theater goer, I had never been to a local Fullerton production, and I have never written a critique of a stage production, so I apologize ahead of time, and you can take this review for what it’s worth.

The Maverick Theater is in the back of a pretty unprepossessing industrial/warehouse building at 110 East Walnut Avenue, and you’ve got to give the Maverick folks a lot of credit – the single scene stage is about the size of my living room, and requires a deft choreography by the director and the cast. The venue lends itself to an extremely intimate relation between performers and the audience – the sort of proximity that lends itself to close study of the actors – for good or ill.

The story itself is the (pretty well known) dark comedy about the battle of wills between the conman Randall P. McMurphy, who has gotten himself committed to avoid a jail work detail, and the control freak-spinster-evil bitch-monster, Nurse Rached, who plays the nuts in the mental ward off each other for her own perverse satisfaction.

The leads are engaging actors; both Brennan Thomas as McMurphy and Julie Patzer as Nurse Rached were able to capture and hold audience attention, although Brennan’s choice of a Southern-sounding accent was a strange affectation in a story that takes place in the Pacific Northwest. I got the strong impression that a lot of Paul Newman in Cool Hand Luke had been injected into the performance, particularly in the scene in which McMurphy chastises his fellows for feeding off of him. Still, Thomas’ rollicking performance was satisfactorily charming and ribald.

The part of Chief Bromden, the Indian narrator in the Kesey book, was played by Enrique Munoz. It seemed like one of the toughest roles in the play, and Munoz essayed it with energy, but ultimately in what I thought was an overly hand-wringing and lachrymal manner that seems to miss something of the Native American character: the overtly disturbed and wounded-child of Bromden’s introspective monologues didn’t seem to translate well into the outward character’s relationship with McMurphy in the Second Act.

The performances of the supporting actors was uneven. David Chorley did a wonderful job portraying the shy and stuttering Billy Babbit; Scott Keister as Frank Scanlon, pulled off an uncanny rendition of Christopher Lloyd’s character “Taber” in the film version. But some of the other parts were performed somewhat awkwardly or overly mannered. The ward attendants just didn’t seem to be able to get into the comic spirit of their parts while the sexually conflicted Dale Harding, as played by Stan Morrow, seemed too much like an over-the-top homosexual caricature.

Although it seemed a bit long, the productions was pretty entertaining and is worth seeing. I’m glad we went. The show runs through February 21.

Using computers to arrange and sort data is useful for all sorts of things – especially when in comes to creating three dimensional imagery. Nobody can deny the impact of presenting scanned data for medical diagnostic purposes; or the use of scaled multi-disciplinary construction models that can simulate a 3D environment: very useful for ascertaining “clashes” between different trades as well as presenting the architect and client with views of his proposed effort.

But despite the technology drum beater’s boosterism (think laptops for kids, FSD style) there reaches a point in every computer application where the information is either too dense or voluminous to be assimilated or analyzed by those looking at it; or is just plain non-effective compared to traditional approaches; or worst, lends itself to misinterpretation or deliberate misrepresentation. This point of diminishing returns is reached quickest when the recipients of data just don’t know what to do with it. When that occurs they’re bound to do something bad with it.

Such may very well be the case with a City of Fullerton program that promises to create a three dimensional model of downtown Fullerton. We received an e-mail the other day from Al Zelinka, who works for the Planning Department. We point out that Mr. Zelinka is very careful to explain that the pilot program is being paid for by SCAG, not the City (where SCAG got the money is obviously not a point of interest for Mr. Zelinka, or, presumably, us).

First, we are inevitably forced to ask why. Who will benefit from the necessary resources plowed into such a program? It’s hard to answer. And who will be able to use the information? We can envisage all sorts of staff (and consultant) time going into creating maintaining and manipulating such data; and then the inevitable jargon and rhetoric tossed back to the public to foist staff driven projects onto the public. The Council: aha! See? The 3D model supports (fill in the name of the Redevelopment Agency’s favored project).

Perhaps the most important question is whether, once the model is done, it needs to be tended and updated by the City. If not, the effort going into seems to be something of a waste.

In any case the public are invited to a meeting on December 16th @ 6 PM in the Council Chambers to see the wonders of 3D modeling. No doubt all of our questions will be answered with sparkling clarity.

At the bottom of his e-mail Mr. Zelinka (AICP) includes a quotation that ought to give pause to even the biggest Planning Department cheerleader:

“Dedicated to Making a Difference.”

“Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir [women’s and] men’s blood….” – Daniel Burnham

Ay, ay, ay!